Cyclone Tauktae: a perfect storm of climate change and pandemic

From May 12-19, in the midst of the devastating second wave of the pandemic, the powerful Cyclone Tauktae struck India’s west coast and killed more than 100 people. This was the deadliest cyclone in the Arabian Sea over the last decade. Starting from southwestern Lakshadweep, the cyclone battered all states on India’s west coast and the remnants caused rainfall even in northern parts of India, Sindh province of Pakistan and Nepal. Its clouds advanced as far as China.

Tauktae is a manifestation of climate change

Climatologically, out of the five cyclones that form annually in the Bay of Bengal, only one develops in the Arabian Sea. But the risk scenario is rapidly changing. A year ago, cyclone Amphan gathered energy from the anomalously high sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Bay of Bengal, intensified, and turned into a super cyclone in 24 hours. A week later, cyclone Nisarga formed over the Arabian Sea and struck the western coast of India. The western tropical Indian Ocean has been warming for more than a century, at a rate that is faster than any other region of the tropical oceans. It is now the largest contributor to the overall trend in the global mean SST. Tropical cyclones draw their energy from warm waters, which is why they form over warm pool regions where temperatures are above 28°C. The Arabian Sea, however, used to be cool, but at the time of the cyclogenesis process of Tauktae, the SSTs in the Arabian Sea were 30-31°C. Tauktae clearly demonstrates the relationship between global warming and the genesis of cyclones.

Tauktae collides with the storm of COVID-19

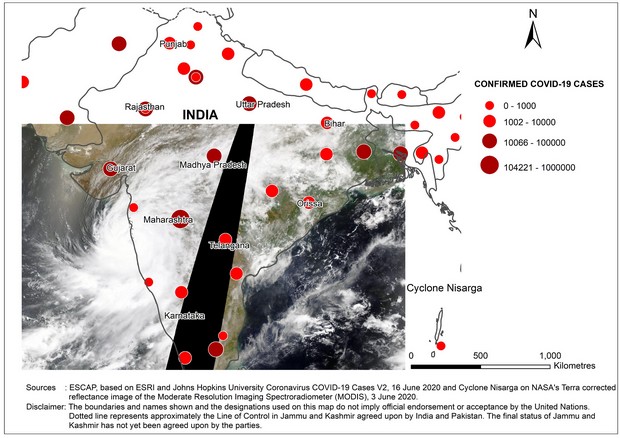

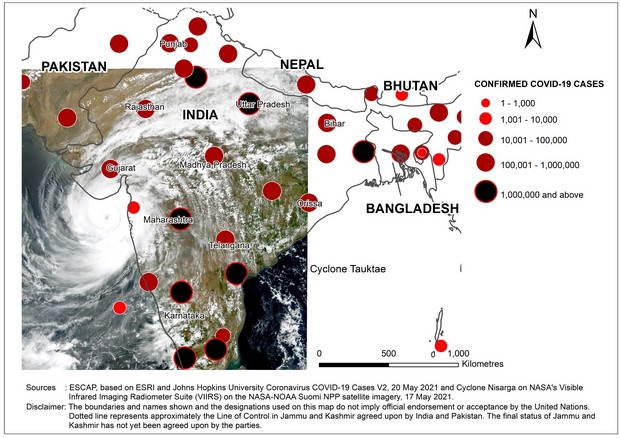

The ESCAP analysis on the intersection of the cyclones Nisarga and Amphan last year, and Tauktae now, with the COVID-19 pandemic, presents a complex and cascading risk scenario. Nisarga struck during the first pandemic wave with limited pockets of infections, but Tauktae hit during the second wave, creating a perfect storm of an extreme climate event and the pandemic. Managing cascading risk scenarios is always challenging. For example, Tauktae struck while India continues to grapple not only with a major spike in COVID-19 cases but also an outbreak of black and white fungus or mucormycosis in the affected states. This forced officials to move hospitalized patients, protect the critical supply chains of medical oxygen and suspend vaccination campaigns. The number of COVID-19 cases remains the highest in the world, with 2.5 million reported during the week of Tauktae’s progression and landfall. While there is no evidence to suggest that Tauktae triggered spikes in caseloads, hundreds of responders that evacuated many at-risk communities during last year’s Amphan and Nisraga cyclones subsequently tested COVID-19 positive. The overlapping crises may spur respondents to eschew protective behaviour, contributing to the spikes.

Figure 1. Collision of Cyclone Nisarga and COVID-19, 18 June 2020

Figure 2: Cyclone Tauktae and COVID-19, 17 May 2021

Sources: The Government of India COVID Resources (18 – 20 May 2021), and Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Data Repository (21 April – 17 May 2021).

Three key lessons emerge for managing cascading risks in the future:

#1. Prepare for emerging risks

Cyclone Tauktae reveals two emerging trends in the disaster riskscape of the region. One, an emerging cyclone risk hotspot in the Arabian Sea, and two, a disaster-health-climate change nexus in the era of the pandemic. Due to the efforts of the Indian Meteorological Department, the early warning for Tauktae was quite precise and also provided enough lead time for the evacuation of large numbers of people at risk during the progression of the cyclone that helped save countless lives. The challenges lie in managing the cascading risks emanating from the interaction of the COVID-19 pandemic with cyclones. The integration of pandemic warning systems with multi-hazard early warning systems for natural and biological hazards will be key.

#2. Build climate resilient infrastructure

Cyclone Tauktae has brought vast destruction along the west coast of India. While the economic cost is yet unknown, infrastructure (power grids, ports and roads) and the agriculture sector are hit the hardest. The cyclone also caused many maritime incidents. In Goa, disruptions in the power sector affected the supply of oxygen to critically ill COVID-19 patients. The Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2019 highlights that a large proportion of existing critical infrastructure is located in multi-hazard risk hotspots. For instance, a third of power plants, ICT fibre-optic cables, and airports, and over 42 per cent of road infrastructure are in multi-hazard risk hotspots. The coastal infrastructure therefore must be made climate resilient through a combination of grey (man-made) and green efforts, including locale-specific nature-based solutions.

#3. Capitalize on regional co-operation

The rapid intensification of cyclones needs to be closely monitored at higher resolution and accuracy using on-site platforms such as buoys and moorings, ocean observation platforms and other innovative systems. Such systems help address the uncertainties associated with the impact of climate change on tropical cyclones. The WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones plays an important role by monitoring and sharing real time data from multiple platforms. It is now time to capitalize on the collective strength of the Panel for managing cascading risks in the Arabian Sea.

Sanjay Srivastava is the Chief of Disaster Risk Reduction at the UN Economic and Social Commission.

Madhurima Sarkar-Swaisgood is Economic Affairs Officer, United Nations.

Sung Eun Kim, Associate Economic Affairs Officer, Disaster Risk Reduction Section, IDD, ESCAP

Maria Bernadet Karina Dewi, Consultant

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

.jpg)

.jpg)