Promoting climate resilience through science: Critical for Asia and the Pacific

Recent research by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has shown that the world is likely to reach or exceed 1.5°C of warming much earlier than previously anticipated. The United in Science 2021 report, launched in September, furthers the understanding of the current state of the earth by compiling the latest climate science drawn from a global network of scientists and institutions, including the IPCC, the Global Climate Project, the WMO, the WHO, UN Environment, the World Climate Research Programme and the United Kingdom Met Office. The report synthesizes and spotlights climate science for actions to accelerate adaptation and resilience pathways.

The United in Science report is significant for the Asia-Pacific region as losses from disasters continue to undermine the region’s economic growth and ability to reduce poverty and inequality by 2030. In many countries, poor households that depend on agriculture employment are more likely to be situated in high multi-hazard risk areas. They are, therefore, not only the hardest hit, but also excluded and disempowered, making it critical to protect these most vulnerable populations from climate risks. The ESCAP SDG Progress Report 2021 found that the region fell short of its 2020 milestone for the SDGs even before the onset of the global pandemic. Currently, less than 10 per cent of the SDG targets are on track to be achieved by 2030. Most alarming are regressing trends on climate action (Goal 13) and life below water (Goal 14), as well as stagnation for life on land (SDG 15).

In preparation for the High-Level Forum on Sustainable Development 2022, the 9th Asia-Pacific Forum on Sustainable Development is an opportunity for countries to review the progress and continued implementation of SDG 14 and SDG 15 from a climate resilience perspective. In this regard, three action points are outlined below:

Build on the science of climate scenarios: The ESCAP Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2021 presents climate scenarios of regional, sub-regional and national “riskscapes,” based on the interactions between natural and biological hazards under the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5 and 8.5 (moderate and severe climate change scenarios). Additionally, the ESCAP Asia-Pacific Disaster Resilience Network, has developed the Risk and Resilience Portal, which uses “riskscapes” to derive the cost of adaptation for natural and biological hazards under the different climate scenarios. The adaptation and resilience matrices are composed of five adaptation priorities: multi-hazard early warning systems, resilient water infrastructure, making new infrastructure resilient, improving dryland agriculture and protecting the mangroves, with weights derived based on the respective climate “riskscape” at different levels. These matrices allow countries to prioritize action and investment in the areas most applicable to their climate adaptation. In South-East Asia, for example, the top adaptation priorities are protecting mangrove forests and making water resources management more resilient, followed by strengthening early warning systems and improving dryland agriculture as well as making new infrastructure climate resilient.

Protecting coastal ecosystems (SDG 14): the specific target of SDG 14.2 on sustainably managing and protecting marine and coastal ecosystems is directly related to strengthening coastal resilience. Mangroves, for example, reduce the impact of tropical cyclones, storm surges, coastal flooding and erosion, while also having carbon capture capacities that exceed land-based forests. Mangroves can therefore mitigate the risks of tropical cyclones and sea level rise induced by climate change.

The ESCAP Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2021 estimates that the current mangrove cover limits the economic impacts of tropical cyclones in many countries of the region. Mangroves have played an essential role in protecting China, India and Viet Nam from tropical cyclones, halving the possible annualized average losses. Ecosystem-based or nature-based adaptation is of growing interest as these solutions recognize the natural protection provided by coastal ecosystems. In 2019, most mangroves in Asia and the Pacific were in South-East Asia, at 58 per cent, followed by the Pacific at 31 per cent. The countries with most of the region’s mangroves were Indonesia at 38 per cent, followed by Australia at 21 per cent, Papua New Guinea and Malaysia at 6 per cent, and the Philippines at 5 per cent. One of the world’s largest mangrove ecosystems, the Sunderbans, spans the borders of India and Bangladesh. Tropical cyclones and related coastal flooding frequently hit this area.

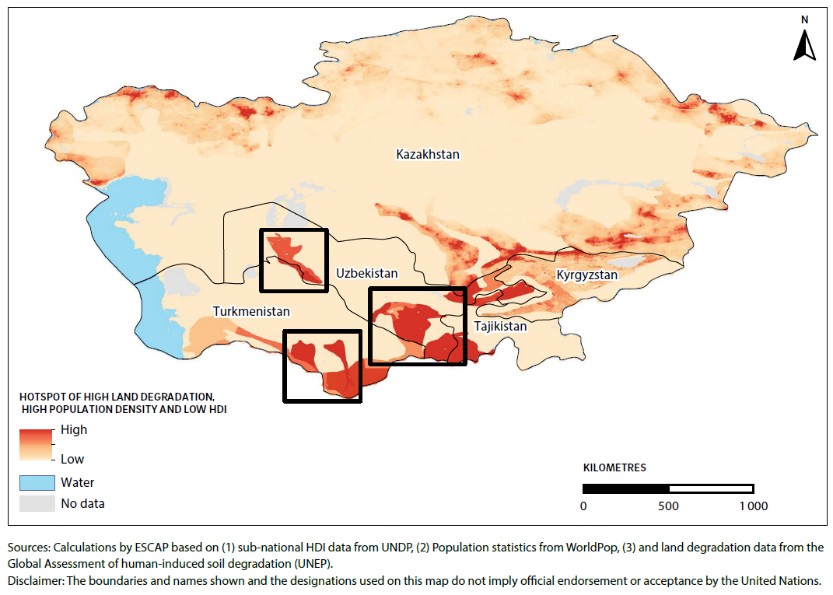

Addressing desertification, land degradation and drought (SDG 15): The relationship between desertification and drought stems from the links between land degradation, climate change and biodiversity loss. IPCC research indicates a substantial increase in arid and semi-arid regions, which are more likely to experience frequent and intense droughts. In North and Central Asia, these areas are expanding in parts of Turkmenistan and Tajikistan where poverty, population density, low human development and drought risk converge (see Figure). The top adaptation priorities in this subregion - confronting land degradation - are making water resources management more resilient and improving dryland agriculture crop production, followed by making new infrastructure more resilient and strengthening early warning systems.

Figure: Land degradation-associated low human development in North and Central Asia.

Moving forward, upcoming subregional preparatory meetings for the 2022 Asia-Pacific Forum on Sustainable Development may want to deliberate the climate “riskscape” approach and create a regional voice at the High-Level Political Forum. Two years back, at the 14th session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, India, for example, committed to restoring an additional 5 million hectares of degraded land by 2030, increasing the land to be restored there to 26 million hectares. Backed by science, such commitments hold the key to closing the gaps towards achieving the SDGs.

Sanjay Srivastava is the Chief of Disaster Risk Reduction at the UN Economic and Social Commission.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI).

.jpg)

.jpg)